The M'Naghten rule(s) (pronounced, and sometimes spelled, McNaughton) is a legal test defining the defence of insanity, first formulated by House of Lords in 1843. It is the established standard in UK criminal law,[1]: 5 and versions have also been adopted in some US states (currently or formerly),[2] and other jurisdictions, either as case law or by statute. Its original wording is a proposed jury instruction:

that every man is to be presumed to be sane, and ... that to establish a defence on the ground of insanity, it must be clearly proved that, at the time of the committing of the act, the party accused was labouring under such a defect of reason, from disease of the mind, as not to know the nature and quality of the act he was doing; or if he did know it, that he did not know he was doing what was wrong.[3]: 632

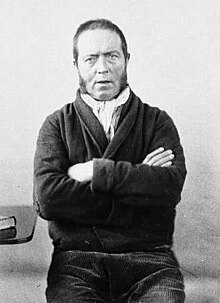

The rule was created in reaction to the acquittal in 1843 of Daniel M'Naghten on the charge of murdering Edward Drummond. M'Naghten had shot Drummond after mistakenly identifying him as the British Prime Minister Robert Peel, who was the intended target.[4] The acquittal of M'Naghten on the basis of insanity (a hitherto unheard-of defence per se in modern form) caused a public uproar, with protests from the establishment and the press, even prompting Queen Victoria to write to Robert Peel calling for a 'wider interpretation of the verdict'.[5] The House of Lords, using a medieval right to question judges, asked a panel of judges presided over by Sir Nicolas Conyngham Tindal, Chief Justice of the Common Pleas, a series of hypothetical questions about the defence of insanity. The principles expounded by this panel have come to be known as the "M'Naghten Rules". M'Naghten himself would have been found guilty if they had been applied at his trial.[6][7]

The rules so formulated as M'Naghten's Case 1843 10 C & F 200,[8] or variations of them, are a standard test for criminal liability in relation to mentally disordered defendants in various jurisdictions, either in common law or enacted by statute. When the tests set out by the Rules are satisfied, the accused may be adjudged "not guilty by reason of insanity" or "guilty but insane" and the sentence may be a mandatory or discretionary (but usually indeterminate) period of treatment in a secure hospital facility, or otherwise at the discretion of the court (depending on the country and the offence charged) instead of a punitive disposal.

- ^ Law Commission (July 2013). Criminal Liability: Insanity and Automatism (PDF) (Discussion Paper).

- ^ Wex Definitions Team (June 2020). "M'naghten rule". Wex. Legal Information Institute.

- ^ Criminal Law – Cases and Materials, 7th ed. 2012, Wolters Kluwer Law & Business; John Kaplan, Robert Weisberg, Guyora Binder, ISBN 978-1-4548-0698-1, [1]

- ^ M’Naghten's Case [1843] All ER Rep 229

- ^ Asokan, T. V. (2007). "Daniel McNaughton (1813-1865)". Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 49 (3): 223–224. doi:10.4103/0019-5545.37328. ISSN 0019-5545. PMC 2902100. PMID 20661393.

- ^ Carl Elliott, The rules of insanity: moral responsibility and the mentally ill offender, SUNY Press, 1996, ISBN 0-7914-2951-2, p.10

- ^ Molan, Michael T.; Bloy, Duncan; Lanser, Denis (2003). Modern Criminal Law (5 ed.). Routledge Cavendish. p. 352. ISBN 1-85941-807-4.

- ^ United Kingdom House of Lords Decisions. "DANIEL M'NAGHTEN'S CASE. May 26, June 19, 1843". British and Irish Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search